Horizon: Zero Dawn is an incredibly impressive game. I was consistently blown away by this game’s world, story, and technical achievements. Nothing in Horizon feels like a huge fatal flaw, and we should look to this game and learn how it does so many things right. However, something ultimately felt missing from Horizon, and kept it from having the lasting impact I felt it deserved.

Note: This analysis will not contain any major spoilers for the story, although there will be minor spoilers as I talk about characters and minor plot points that aren’t introduced until later in the game.

Starting Off With a Bang

When you first start playing Horizon, you’re treated to a great opening cinematic, and I want to talk about why this cinematic works so well. The opening of Horizon is a great example of how to set up a story and hook an audience right from the start.

When you first start playing Horizon, you’re treated to a great opening cinematic, and I want to talk about why this cinematic works so well. The opening of Horizon is a great example of how to set up a story and hook an audience right from the start.

A lot of stories try to open with an “exciting action sequence” to hook you in, and yet more often than not I find myself bored by these openings rather than excited. Action scenes are a climax, they are a point where all the conflicting ideals and goals of the characters come together in violence. We worry for our favorite characters. Will they make it out alive? What will the lasting implications of this fight be?

However, when a story tries to open with an action scene, these elements haven’t had time to fall into place yet, so it often falls flat. Now I’ll admit that openings can have action and it can be interesting, but that is usually because the scene is introducing us to interesting characters and an interesting setting.

Horizon’s opening does a great job of setting up the characters and the world in a very captivating, yet peaceful way. We are introduced to Rost, who is a huge bear of a man. Through excellent animation and voice-over work, we can see that he deeply loves the baby girl in his care. We see the unique clothing and culture of the people in this world, people who are clearly a primitive society, yet adorned with pieces of discarded technology. We’re stunned by the amazing visuals of a ruined civilization, and we immediately want to know more about this world. Rost’s monologue to the baby Aloy reinforces all this.

One of the best moments of the opening is when Rost passes the machine beasts and talks about them. In this moment, the game introduces one of it’s most important hooks: robot dinosaurs. When Rost speaks of hunting the machines, and says he will teach Aloy the skills to do so one day, the game is making a promise to the player: you will hunt robot dinosaurs in this game. The game also makes several other implicit promises: you’ll get to see more of this world, you’ll find out more about this baby girl as she grows older, etc.

Setting up promises of tone at the start of a story is extremely important, it lets the audience know what to expect in the story, even though the story may not contain those elements yet. In many cases it can take a long time for a story to really get to the heart of what the story is about as the main character grows from their humble origins into a great warrior, or whatever the story is about.

It may seems obvious that all these things will happen in a game, especially when you go into a game knowing quite a bit about it already due to marketing and word of mouth, but to rely on that is dangerous. When playing Persona 5, I had no idea the game was going to be about forging friendships, hanging out with my friends, and romancing cute girls. The opening of Persona didn’t promise any of these things to me, and I didn’t go into that game with any advanced knowledge. Looking back on Persona, I think this is a major reason why I disliked the start of that game so much: I didn’t know what I was looking forward to. When I later played other Persona games, I knew what to look forward to, and enjoyed those games much more.

Horizon’s continues its strong start after that cinematic, the entire sequence of controlling Aloy as a child serves as excellent world building, as well as teaching the player how to play the game. It’s a very strong opening and should be studied by game designers looking to learn how to open a game and teach the player.

Setting and Mystery

The setting in Horizon: Zero Dawn is absolutely awesome. It’s fascinating right from the start, and the game has the confidence to know you are going to care about this world.

The game presents a world where primitive cultures have formed among the ruins of a long dead advanced civilization. This ancient civilization has left behind technologically advanced ruins, but most importantly, it left behind robot dinosaurs. Honestly, Horizon will always be known as the robot-dinosaur-game.

Very early, the game sets up the mystery of why the ancient civilization has fallen, and ties it into Aloy’s character, which is very smart, as the exploration of the world and of Aloy’s character is one and the same. The game does a good job with tying together Aloy’s motivations with our own motivations as players: both of us want to explore the world, see what wonders are in the game, and uncover the mysteries the game presents. Several games fail to make the player share the motivations of the protagonist, and struggle as a result.

Imagine a game where the protagonist’s wife dies in the opening cinematic. Literally dying within the first 30 seconds of the game. In this hypothetical game then, the main character’s motivation for the story is revenge. However, as the audience we won’t care about his wife, we never knew her, we spent 30 seconds with her, and so we will feel disconnected from the main character’s motivation. Situations like this happen all the time in story-telling. Books and movies have always struggled with this problem historically, but it’s particularly problematic in games, where we actually control the main character and feel that they represent us. If the “us” that is represented has motivations we have no sympathy to, then we disconnect from the story entirely.

Many other open world games particularly suffer from this problem because the main character wants to accomplish something in what would presumably be a time-sensitive situation (saving somebody in Fallout 3 and 4, Witcher 3, Oblivion, to name a few), but instead as players we want to take our time to explore the world and do side quests. As a result, these games start to feel a little bit silly as the characters around us talk about “time being of the essence”, while we’re instead taking our time to collect stray chickens.

I’m happy to say Horizon does a great job with aligning Aloy’s motivations with our own. Aloy’s motivation is to explore the world, discover the truth of her past, and help people. That’s exactly what we want to do too: we want to explore, solve mysteries, and do side quests.

Chris Avellone, the game designer and writer for many excellent story-based games such as Planescape: Torment, once said that he believed that stories where the protagonist’s motivations were very personal and selfish worked best for storytelling in games, rather than typical “save the world” type plots, and I agree completely. Humans just don’t really care too much about the fate of an entire fictional world, (although I think you could get them to care by focusing on how it will affect all the characters they’ve grown attached to), but humans do care a lot about themselves.

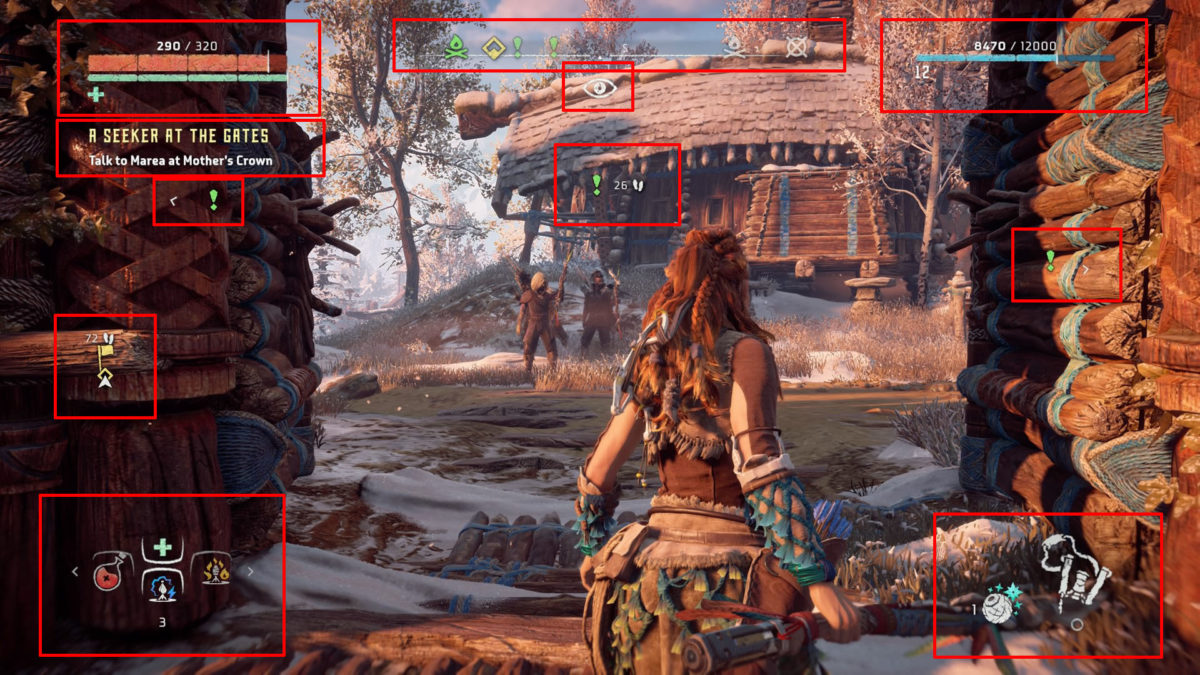

UI Clutter

The first real flaw with Horizon is that the UI is really overwhelming. The game is constantly highlighting nearby points of interest, waypoints, items, and plants on the ground (both on the compass and in the gameworld itself). In addition, there’s a lot of UI elements on the screen such as your experience bar, health, items, ammo and quest objectives all competing for your eyes’ attention on the screen.

That’s a fair amount of stuff on the screen drawing your eyes away from where we really want the player’s attention, which is on the gameworld itself. The icons for waypoints, quests and areas of interest are particularly distracting, they move around the screen a lot as you move, and they zip around the edges of the screen when you walk past them.

Horizon gives you a lot of customization options for the UI, and I felt so overwhelmed by the default UI that I quickly adjusted it. I appreciate that the game gives you these options, but I felt that the default should have been good enough that I never even went looking for these options.

For starters, I think as designers they should choose either the floating icons or the compass, and rely on just the one. I personally like the compass more in that case, because it’s always in one spot on the screen so your eyes don’t get unintentionally drawn to it as much; when icons appear right in the center of the screen you can’t help but be distracted by them.

I also feel that the experience/level bar really doesn’t need to be there except when you actually gain experience, and the health bar similarily only needs to be shown when in combat or low on health. These are all possible options you can set, but they aren’t the default. I disagree with that decision, a lot of players aren’t ever going to change it from the default, lowering their experience without realizing it.

In fact, I would change how experience is shown entirely, only showing it after a fight was over, making it much larger and having more ceremony to it, commemorating that the fight is over and making the player feel more rewarded. If the player really wants to know their exact experience points, they can check in the menu. In a game like Horizon, where the real progression is the story rather than leveling up, I don’t think we need to constantly remind the player exactly how close they are to the next level-up with the actual numbers (and numbers in UI are particularly distracting).

I don’t really have an issue with the icons in the lower left and right; the bottom of the screen is my favorite place for any UI elements, especially in a 3rd person game. It’s very unobtrusive since the player is already mentally blocking out that part of the screen because their character is there. One minor improvement that I would like to see would be to remove the numbers, replacing them dots or some sort of other iconography. This is just because numbers and letters are naturally distracting (people tend to keep trying to read them), so it’d be a nice bit of polish.

In a game where the environment is as beautiful as Horizon, I really want to minimize anything that distracts from looking at the world and takes me out of the experience. All these UI elements cluttering the screen do just that.

Let’s Talk About Maps

There’s something else that Horizon does that I want to talk about, because as these sorts of open world games become more popular, this issue is starting to get out of hand.

All these games absolutely litter their maps with icons.

I personally first started noticing this trend in with the Assassin’s Creed series, and it seems to be steadily growing worse, to the point we are today, where Horizon’s map is completely covered with icons.

Obviously, those icons are there because the game designers want the player to know when there’s various points of interest on the map, but some restraint needs to be shown. I don’t think the map needs to show every group of enemy machines in the game, for instance. Compare Horizon’s map to Zelda: Breath of the Wild’s map: Zelda has no fewer points of interest, yet the game has the discipline to only show the absolute essentials on its map.

I’m personally a big fan of maps looking hand drawn and existing within the world, such as in Thief: the Dark Project. The maps in that game are drawn by the main character and act as a window into the world, giving it more dimension, and represent the main character’s understanding of the world. In this case, the map being covered in notes for the locations of points of interests enhance the game rather than detracting from it.

The reason I get so frustrated with these over-saturated, icon-covered maps is because they undermines our exploration of the world.

Hand-holding and Undermining Your Primary Aesthetic

The primary player motivation for a story-based, open world RPG like Horizon is exploration: the basic human impulse to seek out something new. This is what makes us want to play the game, on a fundamental level.

When playing this game, I remember walking along and seeing a strange shape in the mountainside. I went to check it out and I found a locked door to a giant facility in the mountains. When I managed to find my way inside, there was a whole underground dungeon. I was amazed! I had found this completely hidden dungeon, and fought this amazing boss at the end!

…And then when I beat the boss I got a Playstation Achievement Trophy, and when I checked my map I realized that the map was littered with icons of these dungeons, I had just never noticed within the mess of all the other icons.

That completely deflated the experience for me. The feeling that I had found a hidden secret in the game disappeared.

At the core of the concept of exploration is the idea that you’re finding something for the first time. Of course, in the back of our minds we know other players have found it before, and beyond that, it was put there in the first place by the developers, but we look past all that when playing a game and the experience feels special to us. However, when we get an achievement for finding a “secret”, we’re reminded of the reality that the developer put it there, it takes us out of the moment, and it devalues our experience. Suddenly it’s not a hidden gem we found all by ourselves, it’s just another mark on a checklist. When an icon pops up showing us where a secret dungeon is, we didn’t find it because we had a keen eye, our UI found it for us and the developers are pointing it out to us so we don’t miss it, like a child pointing out to their parents all the things they’ve done because they want their attention.

Unfortunately, I understand that the developers are forced to include achievements for the games they release on consoles, they don’t have a choice. Sadly, I also think we’re at a point where if the developers didn’t included achievements for finding various secrets, people would complain. But I think those complaints would be uneducated.

Exploration is Horizon’s “primary aesthetic”. It’s the main thing that’s making us play the game, and it’s very important to take great cares not to undermine it. It doesn’t ruin the game by any means, but it lessens it subtly. Zelda: Breath of the Wild is a great example of making sure not to undermine the feeling of exploration with its UI and mechanics: it often makes you physically look at and locate objectives, and doesn’t give away the location of something until you’ve already found it. The game doesn’t mark most things for you, it expects you to mark them yourself. A large part of why that game succeeds is that it never undermines its primary aesthetic.

Combat

The combat in Horizon heavily focuses on stealth, and I really liked this direction, it’s very appropriate to the world and Aloy’s character: she’s a hunter. The machines that inhabit the world are basically the world’s wildlife, and they range from all sorts, some are docile herd “animals” that will run if spooked, whereas others are predators that will attack you on sight. Sneaking up behind an unsuspecting machine (or human) and taking them down from stealth is satisfying, as is lining up the perfect arrow from a hidden vantage point.

The combat in Horizon heavily focuses on stealth, and I really liked this direction, it’s very appropriate to the world and Aloy’s character: she’s a hunter. The machines that inhabit the world are basically the world’s wildlife, and they range from all sorts, some are docile herd “animals” that will run if spooked, whereas others are predators that will attack you on sight. Sneaking up behind an unsuspecting machine (or human) and taking them down from stealth is satisfying, as is lining up the perfect arrow from a hidden vantage point.

I particularly liked how since I was (mostly) fighting machines with AI, I never minded “gaps” in their AI behavior. Rather, those sorts of gaps in the AI made them feel more “artificial”. For instance, the sentry machines in a herd are linked to every other machine in the herd, so if a sentry machine spots you it will alert them all. However, if you destroy the sentry machines, the other machines will walk right by a destroyed fellow machine and never realize anything is wrong. In most stealth games you’re fighting humans, so any gaps in the AI really break the immersion. Instead here they enhance it! Of course, you fight human opponents in Horizon too, and for the most part their AI is quite good (they do notice dead bodies of friends), but I particularly enjoyed stealth with the machines.

Horizon’s melee combat is pretty standard for a 3rd person action game, and it works fairly well when fighting small enemies like humans or small machines, but it really starts to fall apart after that. The camera can’t really keep the large enemies within the frame if you’re in melee range, and you tend to suddenly get hit by attacks you never saw telegraphed. The game doesn’t encourage you to use your melee weapon though: there’s no variation in melee weapons and you can only minimally upgrade the spear you start off with, so its damage becomes very underwhelming. The spear also can’t reach the “components” of larger machine enemies either (basically their weak spots). The game clearly doesn’t want your focus to be on melee combat.

Rather, the gameplay pattern the game encourages for fights where stealth isn’t an option is to dodge attacks and then aim your bow at the machine’s components as you create distance from them. Unfortunately, the PS4’s controls let down the game, as aiming at a moving target so quickly with a console controller is awkward. Horizon also falls into the same problem that a lot of 3rd person action games fall into, where combat becomes a constant roll-fest as you roll around to avoid attacks until you have an opening, to the point where it becomes tedious and absurd.

By far the worst aspect of combat though comes when fighting aerial enemies. The camera’s maximum pitch values were just never meant for tracking aerial enemies, and the nature of the camera controls is that it behaves very unintuitively when rotating while looking upwards. Thus, fighting airborne enemies becomes extremely frustrating as you get attacked from directions you can’t even see, and you can rarely hit them back.

Horizon’s combat is at its best when you are sneaking around, stalking your prey like a hunter, and the game knows it, the majority of the combat falls under that style. The times where the game goes into “boss battles” are fortunately few and far between.

Holy Shit This Game Is Pretty

This is a site that’s about game design, so I don’t normally talk about the graphics in a game unless it affects design, but it bears mentioning: holy shit this game is pretty. The artists and engineers of this game need to pat themselves on the back, because Horizon is gorgeous, and not only is it gorgeous, but it runs impeccably. After playing Black Desert, a game which is also visually impressive but filled with technical issues like lag and horrendous level-of-detail pop-in, Horizon was a joy to experience. It’s a testament to the graphics of this game that I used an actual in-game screenshot for the banner image above, when every previous banner has used promotional art.

I’m sure there’s websites that talk about art or engineering that are going over Horizon and talking about improvements the game could make, just like I’m going to be with the game design, but from a layman’s perspective they are absolutely brilliant.

Seriously, it’s a Good Game, Okay?

Looking over my notes of Horizon, there are all sorts of compliments for the game:

The controls are responsive, and button layout always felt intuitive to me.

The sound design is great, the world around you sounds alive, the machines make distinct noises and have well thought out audio cues for all their actions. The musical score is evocative.

The difficulty curve is smooth, presenting a challenge without being overly frustrating.

The art style has a perfect blend of realism and art, faces look real without falling into the uncanny valley. Facial animations alone in this game convey emotion, something most games struggle to do.

For all the minor flaws I brought up before, none of them cripple the game whatsoever. I could go on and on about why this game is great. I won’t. There’s something more important I need to talk about, more fundamental to our ability as game designers to understand.

Humans Are Naught But A Collection Of Memories

Horizon: Zero Dawn blew me away while I was playing it.

And yet, I didn’t love it.

Months after I played Horizon, I didn’t have strong memories of it, and it never really left a lasting impression. While I’ve talked up to this point about the game’s UI, graphics and game mechanics, the real heart of this analysis that I want to talk about is this lack of a lasting impression.

I remember talking to my friend right after I had just finished Horizon, and I was gushing about the game. She then told me something that shocked me: she rated Horizon a 7 out of 10, and rated Persona 5 a 9.5 out of 10. I was flabbergasted. This game, a mere 7 out of 10? I hadn’t played Persona 5 yet, and she had been trying to convince me to, so I figured she was exaggerating. At the time of playing Horizon, I felt it was among the best games I’d ever played.

Unfortunately, as time has moved on, I understand my friend’s evaluation more and more, my memories of Horizon fade, and I think that several years from now, I’ll probably have forgotten about it entirely.

I wanted to do this analysis after I had done my Persona 5 analysis because they are such great examples of games on the opposite sides of a spectrum: Horizon is nearly flawless and yet I never fell in love with it, Persona 5 has horrendous flaws and yet I fell completely in love with it.

The rest of this analysis is my attempt to examine why.

The Iceberg Metaphor

World building in fantasy settings is often compared to an iceberg: the author shows us the tip of the iceberg in the story, but beneath the water’s surface there’s far more, hidden from view. We can only faintly see it, but we know it’s there, and that reassures us that the iceberg is bigger than the small tip that we see.

World building in fantasy settings is often compared to an iceberg: the author shows us the tip of the iceberg in the story, but beneath the water’s surface there’s far more, hidden from view. We can only faintly see it, but we know it’s there, and that reassures us that the iceberg is bigger than the small tip that we see.

The “trick” of world building is that there isn’t actually an entire iceberg. The author can’t possibly create an entire world in rich detail, but that’s fine. Instead, they create enough hints at a larger world that the audience fills in the rest with their imaginations.

At the start of Horizon, we see the iceberg tip in front of us, tantalizing us. Why did the world end up this way? What’s the world like outside of Aloy’s small area of comfort, beyond the boundaries of the sacred lands? We are eager and set off to explore the iceberg.

The problem is that by the end of the game we actually see the entire iceberg, and we realize how small it actually was all along.

Part of the problem is with how the game presents its setting. By the end of the story, the entire world feels like there were about a dozen people (both living and dead) that ultimately mattered to everything that happened in the world. Not only that, but seemingly everything that ever happened of any importance all happened in this one valley. Because this is a game, you see everything in this valley in it’s entirety, and while it’s an extremely expansive setting for a video game, it’s quite small in the grand scheme of a world, and you never really get the impression of a larger world outside of what you see in the game.

Compare to The Witcher 3, which is always telling you about a much larger world beyond what you see in the game. That game doesn’t let you go to these places, Geralt will simply turn around if he goes too far out of the map’s bounds, but you feel that in the world of The Witcher, there’s a much, much larger world out there.

I appreciate that Horizon’s story answers all the questions that it poses, but maybe things wrap up a bit too nicely, everything explained too cleanly. By the end of the story there’s no mystery left, and I feel like I’ve seen everything in this world. Unfortunately, by the end of the game I had no more interest in discovering more about Horizon’s setting or history. I knew it all. When an expansion DLC was announced, I was surprised by how little I cared, and that’s really a shame.

The Danger of Passable Characters

Most of the characters in Horizon are unfortunately pretty forgettable. Aloy is the obvious exception, Aloy is a very well realized character, with a likable, well defined personality, and a history full of rich mysteries that the player uncovers.

Rost, who you see at the very start of the game, is the other standout character. His defining character trait mostly seems to be how much he loves Aloy, but because we like Aloy so much we also come to like Rost too. The voice acting and animation carries a lot of the weight here, really selling the character well. Rost also benefits from the iceberg effect, we don’t get to spend much time with him, but he always has hints of a larger life and personality beyond what we see, so I came away feeling like he was an interesting, rich character.

After Aloy and Rost however, the quality of characters fall off fast. Don’t get me wrong, all the other characters feel very real; rather, my issue is they were all very forgettable, and I was never interested in them.

I have a belief that characters (and setting) need to go beyond merely “interesting”, they should be “super-interesting”. Just giving them traits and personality quirks that would be appropriate for a real person isn’t enough, you need to go even further beyond, particularly in the fantasy genre. Horizon is actually a great example of doing “super-interesting” well with its setting, but when it comes to characters it falls flat.

Erend is a major character in Horizon. If I were to describe him, I’d say he is a man who feels inadequate to fill in her sister’s shoes as captain of the guard after she goes missing. He starts off pretty cocky and tries to impress Aloy with his status, but later feels humbled by her.

Okay, Erend sounds like a believable human. If I met him in real life he’d be fairly interesting I’m sure.

For comparison, let’s describe Morte, a major character in Planescape: Torment. Morte is a fast-talking floating skull, who has apparently been a sidekick to The Nameless One for a very long time. He’s constantly cracking tasteless jokes. He’s the horniest skull ever, immediately making necrophilia jokes about female zombies as soon as you meet him, and constantly begging for money so he can buy prostitutes… apparently undeterred by his complete lack of genitalia. While at first Morte seems to be a loyal ally of The Nameless One, over time you realize the mountain of lies Morte has built: Morte is a pathological liar to his core, misleading The Nameless One from the first words out of his mouth to get on his good side, in constant fear of what The Nameless One will do to him if he ever learns the truth. Did I mention he’s a floating, talking skull?

Morte is an example of what I mean by super-interesting. If I met him in real-life he would be completely overwhelming, but as a character in a work of fiction, I love Morte. Honestly, comparing the two doesn’t even feel fair, Morte is exponentially more interesting than Erend, despite how much more work went into creating Erend from a development perspective.

One reason that I came away from Horizon feeling that the characters weren’t interesting enough is also because there weren’t any gameplay mechanics in place to explore the characters more. Bioware’s games, and the Persona series, both have mechanics set up so that you have the ability to really dive deep into your favorite characters, learn more about them, and develop relationships. As a result those games have so many more opportunities to expand on a character and make them interesting, because the game’s mechanics set up the writing for success. You can talk to the characters in Horizon, but you’ll only get shallow dialog trees relating to the current plot point, you never get to explore them further.

This can all come across as very nit-picky, after all it’s not like the characters are holding back Horizon from being a good game, but when looking for the reasons why the game left a weak lasting impression, I think it’s a very important missed opportunity.

The real danger when making art isn’t making something that’s obviously bad, it’s making something passable but forgettable.

No Bonding Moments

I’m a big fan of “bonding moments” with characters, times that we see the characters outside of the main plot and get to be with them during more mundane moments in their lives. Seeing a group of characters sharing a drink together, or playing a silly game, something outside the combat focus of the main plot. Sometimes in a story these can feel really forced in, but when done well they really make us bond with the characters.

Some memorable examples from some games I’ve played:

- All the witchers getting drunk and trying on witches’ clothing in The Witcher 3.

- The cross dressing pageant in Persona 4.

- Ann desperately trying to stall for time to avoid nude modelling in Persona 5.

- The “date” with Papyrus in Undertale.

All these moments made me laugh along with the characters and made me grow attached to them more. As a matter of fact, Persona is literally built on bonding moments, every major character has at least ten, it’s a mechanic of the game.

The only “bonding moment” in Horizon that comes to mind is the opening sequences, where Rost cares for and teaches the young Aloy. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that these were the two characters that I felt were the strongest.

Imagine a sequence where Erend convinces Aloy to have a drink with him, despite Aloy scolding him for drinking so much. Aloy is very skeptical because she’s never drunk alcohol before, and it turns out she’s a real lightweight and gets tipsy off just a few drinks. Erend, of course, drinks a lot, and starts awkwardly hitting on Aloy. Maybe Aloy flirts back a little. Some sort of silly, drunken conversation happens. It could have been a lot of fun.

We never get moments like this in Horizon though. Now, I can’t claim to have played 100% of the game, and there may be side quests in the game that have some of these moments I’m looking for, but I think it’s telling that when I search on Youtube for “funniest Persona/Witcher/Undertale moments” I get clips of various great moments from those games, but if I search for “funniest Horizon Zero Dawn moments”, I just get clips of Youtubers making jokes while streaming Horizon.

Music

This may be an unpopular opinion, but I would like a different direction for the music. While the music in Horizon is very well done, and it evokes emotion, it’s not memorable. Music can be one of the most powerful triggers for memory in existence, but only if we can actually recognize it later.

I actually have this issue about a lot of game music, and I’m certainly not alone, it’s a common complaint about the modern game industry. In the past, early game systems only had a small amount of processing power and limited sound channels, so the music of those games had to rely on simple melodies, which in turn created more memorable music. We can easily hum these tunes due to their simplicity, and they stick in our heads.

Over the course of this article, I’ve mentioned some other games that I clearly loved, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that I can also remember so many songs from them. If I ever for some reason forget about The Witcher 3, all I’ll ever need to hear is the scream in “Silver for Monsters” and I’ll instantly remember that game. I regularly listen to Persona 5’s “Beneath the Mask” song. Both are modern games that had music with strong, memorable melodies that I remember clearly, it doesn’t need to be the territory of “old classic” games.

I don’t think music with catchy melodies need to be playing all the time in a game, in fact I think that becomes obnoxious very quickly. Sometimes it’s best to have music that enhances the mood and fades into the background, and creating good music of that type is a skill in itself. However, I do believe the game’s main theme, as well as the themes for major characters, should have strong, memorable melodies. Doing so ties music into our memories of the game and its characters, forming strong memory bonds.

Unfortunately, all the music in Horizon falls into the category of “mood enhancing”, leading to an audio experience that is well made but forgettable.

Closing Thoughts

I feel bad for Horizon: Zero Dawn. Here I am beating on it so much, when it’s really such an amazing game and obviously a ton of work was put into it. Despite that however, I can’t ignore that I never loved this game, and it just never left any lasting memories for me. I really wanted to delve into that reaction and figure out why I felt that way in this analysis, because I felt this game should have been one of my favorite games of all time.

I’m a strong believer that it’s important to focus your time on improving the strengths of your game, rather than spending all your time trying to iron out every flaw. Unfortunately, when analyzing a game it’s difficult to keep the analysis from being only critique, it can be a struggle to discuss things that are done well and have much to say about them, it’s much easier (and more fun) to talk at length about flaws. The danger in doing so though is to really miss the point of how to create something that players will care about.

Above, I talked about Horizon’s cluttered UI. Is this a flaw? Yes, and as game designers it’s something we should note so we avoid that flaw in the future. But is Horizon’s cluttered UI actually a problem? Does it take a good game and turn it into a bad game? No.

However, I think the things that led the game into being ultimately forgettable for me are real problems, even though none of them were “flaws”, there were merely “under-performers”.

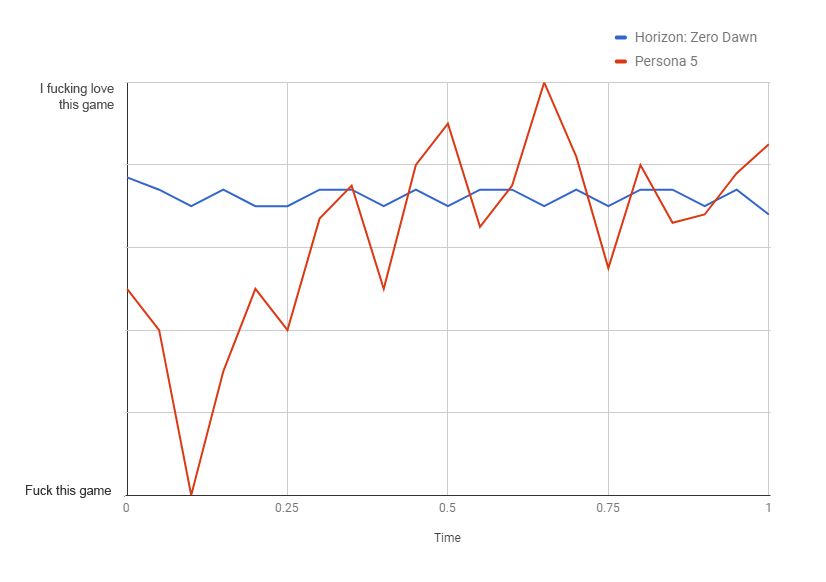

Comparing Horizon: Zero Dawn to Persona 5 is very interesting. Horizon feels like a rock solid game with very little dragging it down, while Persona 5 is filled with frustrations. Yet what Persona does well, it does really, really well, while Horizon is merely a “flawless” game. In the end, I loved Persona in a way I’ll never feel about Horizon.

I’ve prepared an extremely scientific chart that illustrates how I felt about both games while playing them:

I’m sure there’s people out there that absolutely love Horizon: Zero Dawn, and I’d never fault them for that. I didn’t love it though, even though I thought I would.

What We Can Learn From Horizon

So after all that, let’s summarize what can we learned from Horizon: Zero Dawn:

- Creating a good opening sequence does wonders for a game, and is an art in itself. A strong opening doesn’t mean an action sequence, it means to create a interesting opening that hooks the audience.

- Aligning the main character’s motivations with the players is ideal. The player should want to do what the main character is trying to do.

- Keep UI minimalistic, taking up as little of the screen as possible. The best UI is no UI, but assuming that’s not possible, try to get as close to that ideal as you can. UI elements that are only relevant at specific moments should only be seen in those moments.

- Prefer the bottom of the screen for UI elements, it’s less intrusive to the human eye. Keep the top of the screen for critical information.

- Keep in mind what the “primary aesthetic” of your game is, and ensure that your game mechanics and UI aren’t chipping away at it. If your game is about exploration, don’t introduce elements that will undermine the feeling of exploration.

- Characters need to go beyond being simply interesting, they should be super-interesting, and have game mechanics that allow the player to explore those characters further if they wish.

- The bonding moments of characters flesh them out and endear the player to them, take the time out of your story to have these softer moments.

- Music is a powerful stimulant of player’s memories, if that music is memorable. Ask yourself, can this music be hummed, and if so, is that type of music appropriate for this aspect of the game?

- Focus on hitting the important parts of your game out of the park, rather than shoring up every minor flaw.